Real Estate

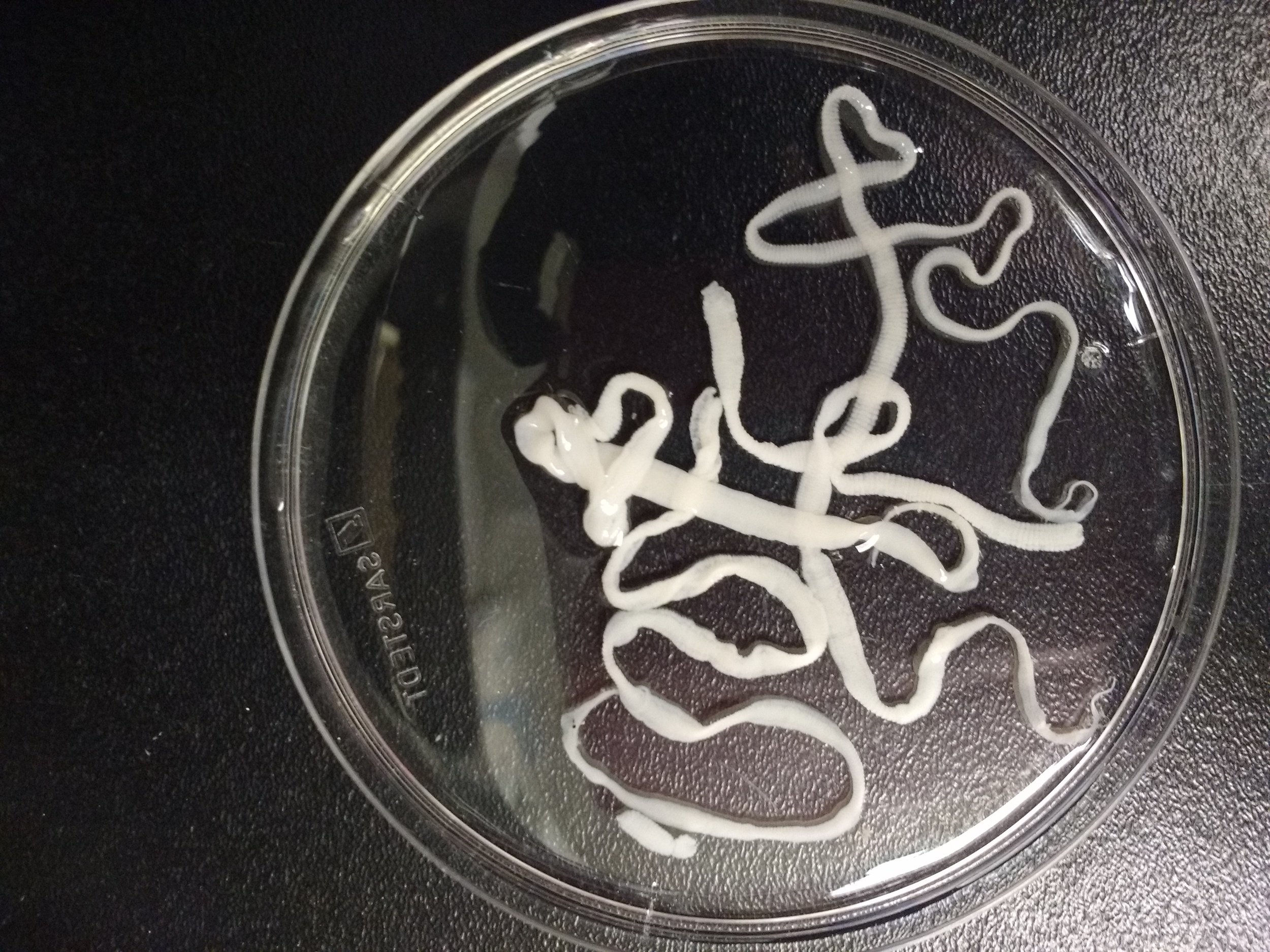

Hymenolepis diminuta, the rat tapeworm

You don’t want to let this one pass you by! Cozy and warm, with over 2700 square feet of living space. Comes fully furnished. Great place to raise a family, with on demand meal delivery services. Must be willing to contend with digestive juices, and bowel movements.

It’s no surprise that the gut is such an attractive piece of real estate for parasites. It’s a passive mode of entry. There’s no need to penetrate a thick epidermis, to access the circulatory system to get to the lungs, like the roundworm Necator americanus. You don’t need to migrate to the salivary glands of a mosquito vector, waiting to be injected into the bloodstream, like malaria-causing Plasmodium falciparum. You just need to be eaten.

Of course there are more than a few hurdles along the way. You need to be eaten by the right host(s), survive the acidic juices in the stomach, and withstand the immune responses directed towards you. But if you can make it to the small intestine of your final host, your dream home awaits. Nutrients are readily available, and when you’ve found a mate and reproduced, you can simply release your fertilized eggs along the gastrointestinal chute, where thousands of your babies are shuttled off into the outside environment.

Parasites possess some of the most remarkable examples of adaptation in the animal kingdom. Being a parasitologist myself, I will admit my bias, but let me take you through a typical lifecycle of one of the most successful gut-inhabiting parasites, the tapeworm, to illustrate my point. The operative word here is typical: there are hundreds of variations. These exquisite adaptations have allowed tapeworms to become one of the most successful colonizers of the gastrointestinal tracts of our planet.

STEP ONE: GET LAID

As a tapeworm egg, you won’t ever be lonely. Thousands of your siblings will keep you company through your journey down the gastrointestinal tract. Once you’ve been shuttled out the back end of your final host, there’s not much to do at this point but wait. Thankfully, you are equipped with a thick egg casing that keeps you safe from the cold, dry conditions in the outside world.

A single tapeworm can produce thousands of eggs every day. Tapeworm eggs are encased in proglottids, specialized segments of tapeworms. Once fertilized, these segments will become swollen with mature eggs, eventually detaching from the adult parasite.

Proglottids are then shuttled out the back end, into the external environment, where it disintegrates. In some species, the proglottid can actually expand and contract, wriggling its way along the intestine, and out of the anus, like an inchworm.

STEP TWO: FIND A RENTAL

You aren’t going to find a rental so much as the rental is going to find you. Parasitologists call this the ‘intermediate host’. Maybe you’ve been accidentally ingested by a grazing deer, alongside some lush grass. Perhaps you’ve been gobbled up by a field mouse. All you can do is hope that it’s a species you are compatible with (or the consequences, for both parasite and host, can be quite lethal).

After hanging around outside for a period of time, being inside the stomach of this animal feels so nice. It’s warmer. Darker. It’s time to hatch. You emerge from your protective casing as a tapeworm larvae.

Thanks to some nasty hooks and suckers, you burrow through the gut wall, and into the beetle’s body cavity. Or perhaps the body cavity of a fish. Or the muscle tissues of a pig. You absorb nutrients through your skin and grow. This can cause significant damage to the host, but there's no need to be too concerned. It’s only a rental. You secrete some molecules that suppress the host’s immune response against you. Eventually, you form a thick protective cyst, which will come in handy later on, and you settle in for a period of stasis, as a metacestode.

STEP THREE: FIND A HOME

Once again you wait. All you can do it hope the right predator comes along to consume your rental host, with yourself inside, much like a trojan horse. Although this time, it’s a bit different. You may be able to stack the deck in your favour.

Not all parasites are able to modify the behaviour of their intermediate host, but many do. Scientists are identifying more and more examples of such parasite modifications all the time. The key is to try and make it a little bit easier for your rental host to get into the belly of your final host. But how?

The bird tapeworm Schistocephalus solidus drives its host, a stickleback, to seek warmer waters. These higher temperatures make it possible for the tapeworm to grow as large as possible, eventually outweighing the host. Ultimately parasitized fish become bolder, more solitary, and less likely to avoid predators. This makes them easy targets for the fish-eating bird for whose guts the tapeworm longs for.

Brine shrimp, often translucent, turn a bright red when parasitized by several species of tapeworm. Infected shrimp swim closer to the surface, making them more likely to be eaten by a wading bird. The tapeworm sterilizes the shrimp, which might account for the behavioural changes. Alternatively this might be a way to ensure that shrimp energy resources aren’t diverted to the costs associated with reproduction, but remain with the shrimp (and thus the parasite) instead.

When the rat tapeworm Hymenolepis diminuta develops a fully mature cyst within its beetle host, infected beetles are more attracted to light, are no longer attracted to sex pheromones. Remarkably infected beetles live longer than their uninfected counterparts, which may increase the likelihood that the beetle is ultimately eaten by a hungry rat.

STEP FOUR: MOVING DAY

Congratulations on your new home! You've been eaten by your definitive host! But first, you must survive a churning, acidic compartment. The mammalian stomach has evolved to be a hostile environment for many organisms, for good reason. Luckily, the cyst you developed when you were still renting protects you. This is why the timing of parasite-mediated host changes are so important. Immature stages of tapeworms are in the process of developing this cyst, and if they reach their final hosts’ stomach too soon, the consequences are lethal.

This tapeworm was cruelly evicted from the intestine of my cat.

Once you’ve passed into the intestine, intestinal juices containing trypsin, a digestive enzyme produced by the pancreas, wash over you. This signals that it’s time to emerge from your cyst, as a juvenile tapeworm. After a big stretch, you wrap yourself around an intestinal villus. You use some suckers to secure yourself against the rhythmic muscular contractions in the intestine that propel food forwards. Since you don't have a mouth or an intestine, you simply absorb nutrients across your skin, and grow.

STEP FIVE: MAKE SOME BABIES

It's time to start a family. While you have both male and female reproductive organs, they mature at different times, so you’ll have to find a mate. This is for the best anyways, as sexual reproduction makes for genetically diverse, and thus more adaptable and resilient organisms. Luckily as a hermaphrodite, any tapeworm you encounter of the same species is a potential mate. You exchange sperm with your partner, and both of you become egg-producing machines. Swollen proglottids, teeming with eggs, detach from your proximal end, leaving the safe comforts of home. The cycle continues.

Slow dancing tapeworms!

It's a long journey for these tapeworms. Many will never find a rental, let alone a permanent home. In some cases, the host immune system can thwart the tapeworm, cruelly evicting it from a warm safe place to eat and reproduce.

The complex life cycles of parasites pose an interesting question: why undergo such an arduous journey, only to end up back in the gut of the same species you started in? You have to admire the tenacity of these tapeworms. Maybe they don't deserve their maligned status. They're just looking for a place to hang their hat, and it's a tough market these days. Come to think of it, do you have any vacancies?